The Cultural Readymade: Ai Weiwei’s Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn

Figure 1. Ai Weiwei, Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, 1995 (printed 2017), Three gelatin silver prints, 148 x 121 cm each. Smarthistory.

In 1995, Ai Weiwei created his triptych photography series Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn. Ai is known for his polemic artworks, often utilizing his platform as a well-renowned artist to criticize the Chinese government’s repressive hold over its people. Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn demonstrates Ai’s critique of the Chinese government, specifically during the time of the Cultural Revolution, where artifacts from ancient China were discarded and destroyed. Although Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn appears to be an act of destruction, Ai’s deliberate smashing of the ancient Chinese artifact is actually an act of preservation by turning the old into something new. Furthermore, his introduction to the readymade and his ventures into the Panjiayuan antique markets in Beijing combined to create Ai’s own concept of the “cultural readymade.” This concept became ingrained into his larger oeuvre, in which he took everyday objects and transformed them into a work of art. In doing so, Ai calls attention to cultural value, how and why people imbue value on certain objects and the erasure of China’s ancient past during the Cultural Revolution.

The three photographs that comprise Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn (fig. 1) were taken by Ai’s brother, Ai Dan, ten years prior to their first public display in 2005. The photographs depict Ai in a series of steps that show the 2,000-year-old urn’s destruction. Starting from left to right, the first image shows the urn slipping from Ai’s fingers, about to begin its fall and ultimate destruction. The second image shows the urn completely out of Ai’s hands and a second away from shattering. The last photograph captures the urn in pieces on the floor with Ai’s hands still in the air. In all three photographs, Ai stares directly at the camera, fully acknowledging his destructive action. Furthermore, the three images create a triptych and a continuous narrative of a seemingly mundane action, yet the urn’s cultural ties to ancient Han China and its survival into the 20th century transform such a blasé action into one of controversy and provocation.

Figure 2. Ai Weiwei, Han Jar Overpainted with Coca-Cola Logo, 1995. H. 25 cm, D. 28cm, ceramics.

Why, then, would Ai Weiwei destroy a 2,000-year-old Han urn that is heavily tied to Chinese history and culture? Although the photographs paint the picture of destruction, Ai believes that his performance of destroying such an artifact is quite the contrary. It is a form of preservation, not destruction. The idea of preserving a piece from ancient history through the means of “destruction” is repeated multiple times by Ai. It is seen in the Han Jar Over-painted with the Coca-Cola Logo (fig. 2) and the Ten Neolithic Vases painted over with bright industrial paint colors (fig. 3). Ai paints over these ancient artifacts and gives them a second life by transforming them into contemporary artworks. In fact, there is a long-standing tradition of collecting and re-purposing ancient artifacts in China. As Tiffany Wai-Ying Beres writes in her article about Ai’s Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, “rulers and elites collected ancient materials and acted to preserve them or emulate them in new works, whether it was preserving important documents by recording them on durable surfaces like stone steles or incorporating ancient designs into bronze ceramics.” Furthermore, Wai-Ying Beres gives the example of a Shang dynasty queen’s burial tomb in which both prehistoric jade carvings and carvings made during her time were discovered, yet the jade carvings produced during her time were “modeled on earlier Neolithic prototypes.” Thus, collecting ancient artifacts has been a long Chinese tradition while also influencing and inspiring the creation of new works of art through their designs. Ai Weiwei’s Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn is, therefore, a continuation of collecting and re-purposing Chinese artifacts by transforming them into contemporary art.

Figure 3. Ai Wewei, Ten Neolithic Vases, 5000-3500 BCE, industrial paint, ca. 35 x 27 x 27 cm.

Furthermore, much of Ai’s work makes use of the readymade concept he discovered while living in New York City. Ai Weiwei moved to the United States in 1981 to pursue academic studies abroad. Traveling to the United States was unheard of at the time, as China’s borders were mostly closed to the West. As Ai states in his memoir 1,000 Years of Joys and Sorrows, “The country had been isolated from the West for more than thirty years... Now, with the resumption of relations with the United States and Europe, I was in the first wave of students going abroad at their own expense.” Hischoice to study abroad in the United States was looked down upon by most people, and it was even considered a sign of defection from China. Despite the controversial decision to move to America, living in New York was a major catalyst for Ai as an artist because the exposure to certain Western artists resulted in him developing his own artistic style. It wasduring his time there that he was introduced to the Dadaist Marcel Duchamp, who is known for his work the Fountain (fig. 4) -- an example of Duchamp’s concept of the readymade.

Figure 4. Marcel Duchamp, Fountain, 1917 (replica 1964). Tate Modern.

Moreover, the readymade is defined by taking already made objects, usually mass-produced objects such as the urinal from the Fountain, and elevating them to the status of art. By elevating mass-produced objects to the status of art, Duchamp challenged the notion of what art is. Other artworks that demonstrate the idea of the readymade is Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s Untitled (Perfect Lovers) (fig. 5). He takes two analog clocks, mundane objects of everyday life, and transforms them into a double portrait of himself and his partner. Artworks that use readymade objects tend to be conceptual. They place the meaning behind the art as more important than its actual appearance. Furthermore, Duchamp’s readymade concept challenged the idea that art must be beautiful and aesthetically pleasing to the eye. Margaret Iversen further discusses the idea of the readymade in “Readymade, Found Object, Photograph.” She claims, “Its effect, its legacy for subsequent art was to shift the artistic ‘discursive field’ away from questions about aesthetic experience and toward questions of what constitutes a work of art.” Moreover, Iversen raises important questions about the readymade, such as “Are aesthetic qualities necessary? Does a replica have the same value as the original work?” Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn addresses such questions by labeling the action of breaking a 2,000-year-old urn as a work of art, not the urn itself. There is no aesthetic appeal in destruction. However, Ai captures the destruction through the lens of a camera, freezing the moment in three distinct stills. Discovering Duchamp and his idea of the readymade, therefore, influenced Ai’s artistic style, while his Chinese identity shaped the content and the larger meaning of his works.

Figure 5. Felix Gonzalez-Torres, “Untitled,” (Perfect Lovers), 1991.

After twelve years of living in the United States, Ai eventually moved back to Beijing in 1993 so that he could help take care of his aging father, Ai Qing. Ai Weiwei had a hard time adjusting to the changes that occurred in the city while back in Beijing. When he left China in 1981, the country slowly opened its borders to the West and other foreign nations, and Beijing grew immensely due to the country’s increasing economy. According to Mami Kataoka’s chapter “According to What -- A Questioning Attitude,” “Ai returned home to China at a time when the country was undergoing major changes and emerging in a new incarnation that prioritized economic development over freedom and democracy.” In order to help his brother, Ai Dan brought Ai Weiwei to the Panjiayuan antique markets located on the outskirts of the city. These markets contain artifacts from various time periods all over China. The Cultural Revolution was the main reason for the large market of Chinese antiques. Objects from the past were seen as “bourgeois, revisionist culture,” -- leading artifacts to be discarded and thrown away and to be no longer praised for their connection to China’s ancient past.

Due to the large market economy in 1993, there was a boom in antique trading. There were little to no fakes at this time since the market economy was so young and prices were very low for high-quality products, therefore making it a gold mine to shop for authentic antiques. Ai viewed China as “culturally impoverished” at this time, yet seeing all the ancient artifacts gave him the realization that art never truly disappeared. These antiques would remain behind long after his death. Moreover, the ideals of the Cultural Revolution -- of destroying the old to rebuild a new culture -- could never fully be accomplished because such ancient artifacts would outlast China’s authoritarian regime. This is where Ai would get the idea of destroying a Han urn -- his first large milestone in defining his artistic style. Combining the readymade with the culture associated with Han Chinese ceramics creates what Ai calls a “cultural readymade.” The act of breaking a Han Chinese urn demonstrates Ai’s perspective toward culture, as in how and why is the value placed on a 2,000-year-old urn? Cultural value is placed on such an object because of its tie to ancient China and its survival into the 20th century. In fact, “The Han dynasty (206 BCE - 220 BCE) is considered a defining period in the history of Chinese civilization, and to deliberately break an iconic form from that era is equivalent to tossing away an entire inheritance of cultural meaning about China.” Thus, by altering the physical appearances of these ancient artifacts, either by smashing them as in Destroying a Han Dynasty Urn or by dipping them in industrial paint, Ai challenges their authenticity as cultural symbols of the Han dynasty and of China’s ancient history. Ai is not destroying these ancient artifacts, as some people view it, but he breathes a new life into these mass-produced, readymade objects that were once discarded during the Cultural Revolution -- allowing them to enter into these artistic spaces.

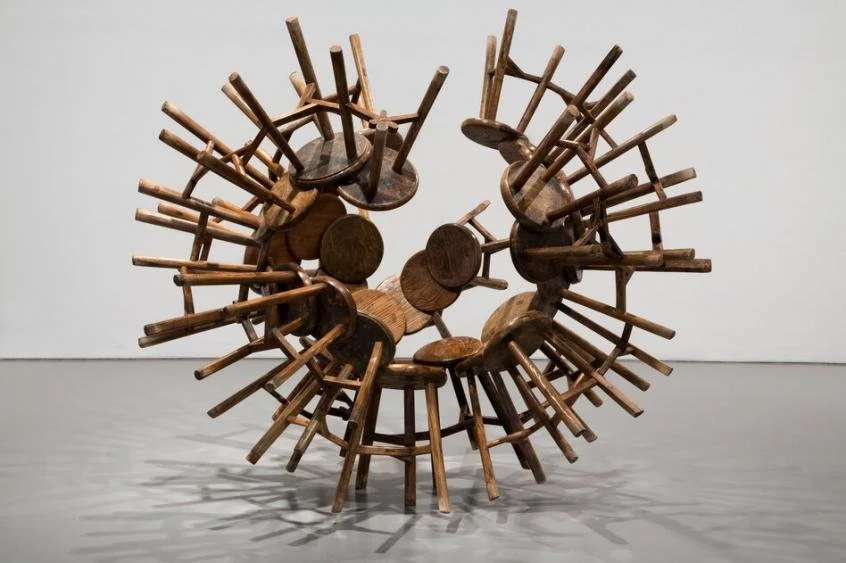

Figure 6. Ai Weiwei, Grapes, wooden stools from the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), HirshhornMuseum.

Using not just Han ceramics but also Qing dynasty stools (fig. 6), Ai demonstrates that there is a constant conversation between culture and consumerism. As he has stated, “My work is always dealing with real or fake, with authenticity and what the value is, and how the value relates to current political and social understandings and misunderstandings.” In relation to Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, the value of Han ceramics increased after the Cultural Revolution. Thus, smashing the Han urn creates a political message -- a message dating back to the destruction of these artifacts during the Cultural Revolution. Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn is, therefore, a play on Mao Zedong’s belief of destroying the old to form a new Chinese culture while also addressing themes of consumerism in Chinese culture.

Both Han urns and Qing stools were mass-produced at one point in time and have close ties to Chinese culture, insinuating that these objects have a value that a readymade object, such as a clock, does not. Altering these objects’ appearances, therefore, alters their cultural value because of their new function. They are removed from their old function of being mass-produced objects of everyday use and are elevated to the status of artwork. As stated by Ai himself, “art should be a nail in the eye, a spike in the flesh, gravel in the shoe: the reason why art cannot be ignored is that it destabilizes what seems settled and secure.” Therefore, breaking a Han urn and capturing its destruction subverts the definition of art while also challenging the viewer’s very notion of cultural preservation, cultural value, and their own definition of art itself.

Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn eventually led Ai Weiwei to develop his artistic style. After discovering Duchamp’s concept of the readymade and combining it with his own Chinese culture and heritage, Ai’s art stands as “cultural readymades.” Like the Han urn, Ai takes mass-produced objects tied to Chinese culture and history and transforms them into contemporary works of art. Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn is more than just a challenge over the definition of art. The destruction of a Han urn, an object with historical and cultural ties to Han China, demonstrates Ai’s discussion of cultural preservation and value while also simultaneously discussing the political climate of the Cultural Revolution.

Article Written by Megan Cassidy

Edited by Brooke Olson

Work Cited : Ai, Weiwei. “New York, New York.” In 1000 Years of Joys and Sorrows, 165-95. Translated by Allan H. Barr. New York: Penguin Random House, 2021.Ai, Weiwei. “Perspective.” In 1000 Years of Joys and Sorrows. 196-214. Translated by Allan H. Barr. New York: Penguin Random House, 2021.Guggenheim Bilbao. “Ai Weiwei, Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, 1995.” Accessed April 24, 2024. https://www.guggenheim-bilbao.eus/en/learn/schools/teachers-guides/ai-weiwei-dropping-han-dynasty-urn-1995. Iversen, Margaret. “Readymade, Found Object, Photograph.” Art Journal 63, no. 2 (2004): 44–57. https://doi.org/10.2307/4134520. Kataoka, Mami. “According to What? — A Questioning Attitude.” In According to What?According to What?, edited by Deborah E. Horowitz, 8-21. Munich: Prestel Verlag, 2012. Tancock, John. “Ai Weiwei – Readymade and Beyond.” Ai Weiwei: In Search of Humanity, edited by Dieter Buchhart, Elsy Lahner, and Albrecht Schröder, 26-41. Vienna: The Albertina Museum, 2022. Wai-Ying Beres, Tiffany. "Ai Weiwei, Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn." Smarthistory. August 25, 2020. Accessed April 24, 2024. https://smarthistory.org/ai-weiwei-dropping-a-han-dynasty-urn/.